|

Extending Routine Traffic Stops Without Reasonable Suspicion is Unconstitutional

Takeaway: a law enforcement officer may not conduct a dog sniff of a car after an officer completes a traffic stop unless an officer can state specific facts justifying the extension of the stop. Rodriguez v. United States: On April 21, 2015, the United States Supreme Court issued an opinion in Rodriguez v. United States, a case where an officer conducted a dog sniff of Rodriguez’s car after completing a traffic stop. In Rodriguez, the officer pulled Rodriguez over for driving on the shoulder of the road, which is a traffic infraction in Nebraska. The officer checked Rodriguez’s driver’s license and issued Rodriguez a warning for the traffic offense. The officer then asked Rodriguez if he could walk his dog around Rodriguez’s car, which he refused. Upon refusal, the officer immediately detained Rodriguez until a second officer arrived at the scene, at which point the officer walked the dog around the car. The dog alerted to the car, which resulted in a search of the car revealing methamphetamine. The traffic stop was extended approximately 8 minutes to allow the dog to sniff around Rodriguez’s car. Rodriguez was indicted on federal drug charges and later sentenced to five years in prison. Rodriguez then filed a Motion to Suppress the evidence seized from his car because the officer detained him without reasonable suspicion of the presence of drugs, which prolonged the traffic stop an unreasonable amount of time (approximately eight minutes). The Motion to Suppress was denied by the magistrate court, district court, and eventually the Eighth Circuit Court. On appeal from the Eighth Circuit, the United States Supreme Court agreed to hear Rodriguez’s case. The Supreme Court found that the officer’s actions violated Rodriguez’s Fourth Amendment rights. The Court held that reasonable suspicion is required to extend a traffic stop and conduct a dog sniff. In other words, without specific facts (more than a hunch) indicating that drugs are present in a car, a dog sniff of a car is not allowed after a traffic stop has been completed. Because of this, under Rodriguez, an officer must be able to state specific facts that indicate drugs exist in a car to extend a traffic stop. If an officer cannot show such facts exist, then a dog sniff conducted after completion of a traffic stop will be considered unreasonable and any evidence seized from the car may be suppressed. The Supreme Court’s opinion in Rodriguez was based off the purpose of an everyday traffic stop. The purpose of a traffic stop, ordinarily, is to address the traffic violation authorizing the officer to stop a car, which includes “determining whether there are outstanding warrants against the driver, and inspecting the automobile’s registration and proof of insurance.” Once the purpose of the stop is fulfilled, the individual pulled over should be allowed to go on his or her way. The purpose of a traffic stop is not to find drugs or “sniff” out other illegal activity. If an officer does not become aware of specific facts that suggest other criminal activity exists during a stop, then an officer may not extend the stop. This is exactly what happened in Rodriguez and what is now considered a violation of an individual’s Fourth Amendment rights.

1 Comment

|

Archives

February 2023

AuthorDevon Wilson, Marketing, PR Categories |

|

Boise Law Firm - Local Map listing

|

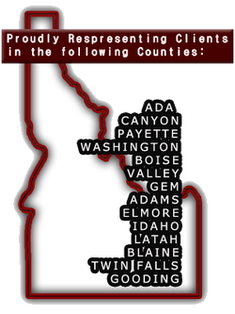

Jeff Nona Attorney at Law - Serving The following Counties in Idaho

Ada County Canyon County Payette County Washington County Boise County Valley County Gem County Adams County Elmore County Idaho County Latah County Blaine County Twin Falls County Gooding County |

READ ABOUT US:

legaldirectorate.com/company/jeffery-e-nona-2083311633-boise/

https://threebestrated.com/dwi-lawyers/jeffery-enona---jeff-nona-attorney-at-law-boise-city-130909058

READ ARTICLES ON OUR BLOG

legaldirectorate.com/company/jeffery-e-nona-2083311633-boise/

https://threebestrated.com/dwi-lawyers/jeffery-enona---jeff-nona-attorney-at-law-boise-city-130909058

READ ARTICLES ON OUR BLOG

If you need help, call Jeffery E. Nona, Attorney At Law today at 208-331-1633 to schedule your free initial consultation.

***The information on this website is for general information purposes only. Nothing on this site should be taken as legal advice for any is not intended to create, and receipt or viewing does not constitute, an attorney-client relationship.

Contact Us | Resources | Terms Of Use | Privacy Policy | Linking Policy | Jeff Nona Attorney at Law - All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed