|

I got pulled over for DUI. Can a police officer draw my blood without a warrant?

Short answer, maybe. A police officer might be able to draw your blood without a warrant, but will likely obtain a warrant before drawing your blood. In April of 2013, in the case of Missouri v. McNeely, the United States Supreme Court held that a police officer is required to obtain a warrant before drawing your blood because your body’s natural metabolism of alcohol doesn’t create the immediate necessity required to permit a warrantless blood draw. However, while police are generally required to obtain a warrant before drawing your blood, there are two situations where a police officer can probably draw your blood without a warrant. First, a police officer can probably draw your blood without a warrant based on the “implied consent” you gave by driving on Idaho’s roads. In other words, by driving on Idaho’s roads you are consenting to a blood alcohol content (BAC) test because of the benefits you receive from using those roads. While there are strong arguments against this theory, some Idaho courts still use it to uphold warrantless blood draws. Second, a police officer is allowed draw your blood without a warrant when exigent circumstances exist. Exigent circumstances are those situations that demand immediate police action. The exigency of every situation is judged on a case-by-case basis with special attention paid to the circumstances that lead up to the situation. So, for instance, a few situations where a warrantless blood draw would be allowed include where you were involved in a car crash or where a child is present in your vehicle. Even if exigent circumstances don’t exist, it’s easy for a police officer to get a warrant to draw your blood. As long as a police officer can show that there is probable cause to suggest you under the influence of alcohol, a warrant can be obtained. Once probable cause is shown, a warrant is only a phone call or two away. Either the arresting police officer or a local prosecutor will call the judge, explain the facts of the situation supporting probable cause, and the judge will normally issue a warrant to draw your blood. However, if a judge does not issue a warrant and the police draw your blood anyway, your Fourth Amendment rights might have been violated and it’s possible that your BAC results from your blood draw cannot be used as evidence against you.

1 Comment

After hearing several questions about whether Idaho’s “rider” program, which incarcerates offenders in a special treatment program for a short time, then releases them on probation if they succeed or sends them to prison for their full terms if they fail, skews state’s incarceration rate as presented in the justice reinvestment analysis by the Council of State Governments’ Justice Center and the Pew Trusts, I quizzed Mark Pelka, the Justice Center’s director. His answer: Riders were only counted as incarcerated when they were actually behind bars, not when they were out on probation. The project’s figures showed that in Idaho, non-violent offenders spend twice as long behind bars as they do in the rest of the nation.

I also asked about sentencing reform, and its role in this project. The answer: The project didn’t even study Idaho’s sentencing laws, as far as the initial sentence that’s issued by a judge. “We have had calls from judges and many others to look more at sentencing,” Pelka said, but, “We did not shine a flashlight on that.” That was in part because Idaho’s sentencing laws don’t differentiate much within categories of offenses, leaving discretion to judges and making Idaho’s sentencing system more difficult to analyze. “Eighty-four percent of sentences are to probation or rider,” Pelka said. Then, 85 percent of riders get released on probation. But the project is recommending one major change to how sentencing works in Idaho: It’s calling for non-violent offenders to serve just 100 to 150 percent of their fixed terms behind bars. Currently, drug offenders in Idaho are serving 219 percent of their fixed terms; property crime offenders, 200 percent; and DUI offenders, 231 percent. The idea is to focus more on supervision of those offenders when they’re initially released from prison, to keep them from going back. “The big challenge for Idaho is the return-to-prison rate,” Pelka said. “Fifty-three percent come back in.” In the project’s recommendations, policy option 2(D) calls for Idaho to “reserve prison space for individuals convicted of violent offenses, by regulating the percent of time above the minimum sentence that people convicted of non-violent offenses may serve.” To accomplish that: “Require that people sentenced to prison for non-violent offenses be paroled at a point between 100 and 150 percent of the fixed term and then be placed under parole supervision.” That would be a big change. Even without making any changes in Idaho’s overall sentencing laws – under which judges now set both a fixed and an indeterminate term, such as two to six years, with the Parole Commission deciding how much of the indeterminate part the inmate serves – the project is predicting $255 million in savings for Idaho over five years. KTVB.COM

Posted on November 17, 2013 at 4:11 PM Updated Sunday, Nov 17 at 4:11 PM BOISE -- Law enforcement agencies around Idaho launched expanded DUI patrols Sunday. The extra enforcement, in conjunction with education campaigns, is set to run through the Thanksgiving holiday. The Idaho Transportation Department's Office of Highway Safety made funds available to local police agencies to pay for the expanded patrols. "ITD's goal is not one death, because every life counts," said Kevin Bechen, with ITD. "We're committed to doing everything we can to help keep families safe and whole." According to ITD, last year, impaired driving contributed to 1,454 crashes on Idaho's highways and caused 73 fatalities statewide. Bechen offered the following tips to make this Thanksgiving holiday safer:

|

Archives

February 2023

AuthorDevon Wilson, Marketing, PR Categories |

|

Boise Law Firm - Local Map listing

|

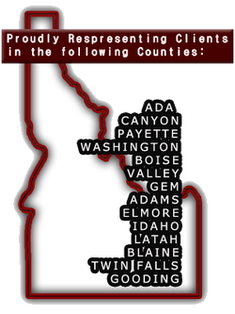

Jeff Nona Attorney at Law - Serving The following Counties in Idaho

Ada County Canyon County Payette County Washington County Boise County Valley County Gem County Adams County Elmore County Idaho County Latah County Blaine County Twin Falls County Gooding County |

READ ABOUT US:

legaldirectorate.com/company/jeffery-e-nona-2083311633-boise/

https://threebestrated.com/dwi-lawyers/jeffery-enona---jeff-nona-attorney-at-law-boise-city-130909058

READ ARTICLES ON OUR BLOG

legaldirectorate.com/company/jeffery-e-nona-2083311633-boise/

https://threebestrated.com/dwi-lawyers/jeffery-enona---jeff-nona-attorney-at-law-boise-city-130909058

READ ARTICLES ON OUR BLOG

If you need help, call Jeffery E. Nona, Attorney At Law today at 208-331-1633 to schedule your free initial consultation.

***The information on this website is for general information purposes only. Nothing on this site should be taken as legal advice for any is not intended to create, and receipt or viewing does not constitute, an attorney-client relationship.

Contact Us | Resources | Terms Of Use | Privacy Policy | Linking Policy | Jeff Nona Attorney at Law - All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed